Steel nerves. Crocodile skin. An iron stomach.

That’s what it takes to work in Hollywood, the land of hopes and dreams. Terrell Tannen should know — he lived the life for 50 years, primarily as a screenwriter, sometimes as a director, but always as someone who, while achieving much success, never quite reached the top of the mountain.

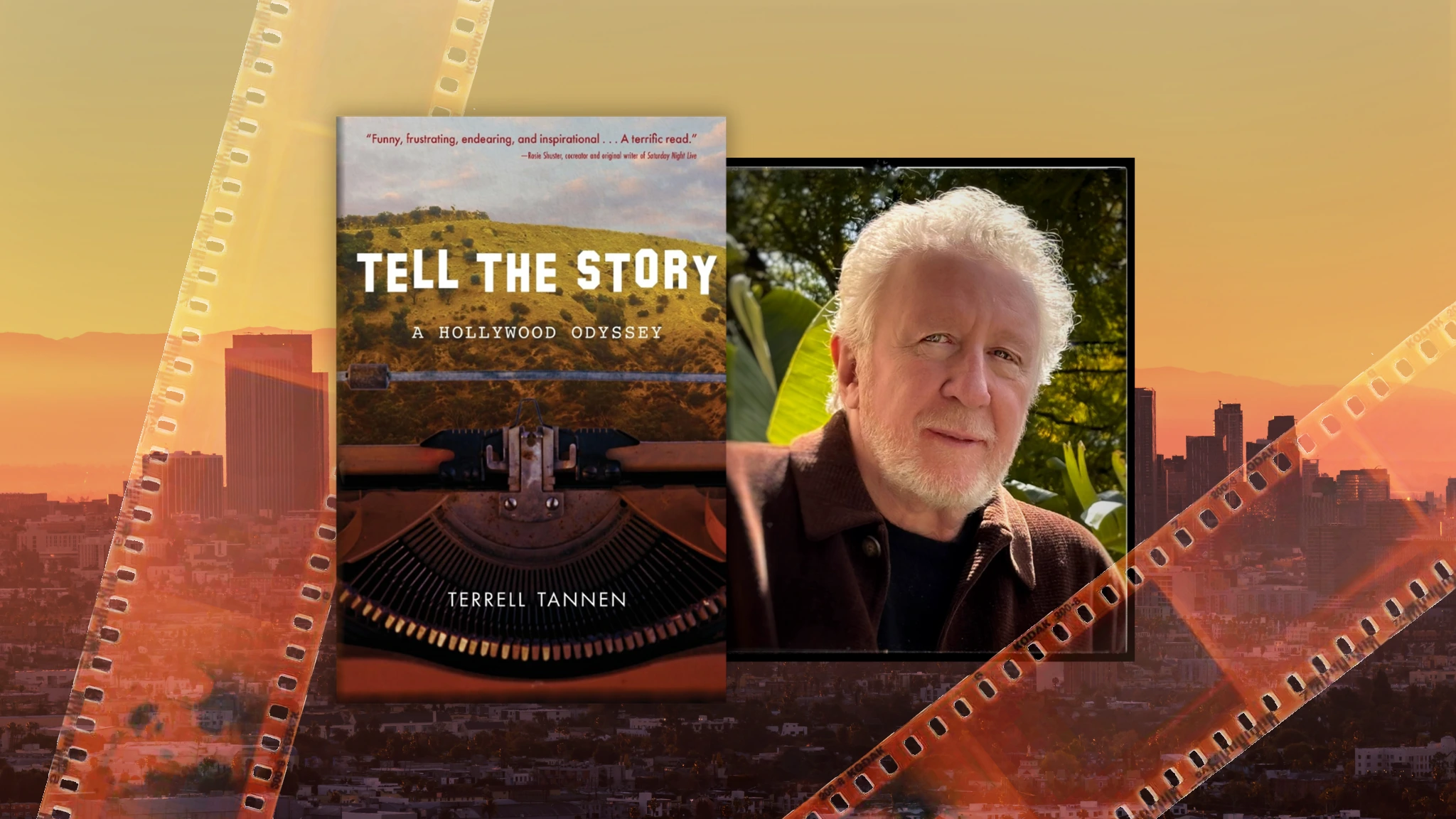

His highs and lows, disappointments and inspirations are beautifully documented in his fascinating memoir Tell the Story: A Hollywood Odyssey.

In this recent Q&A, the author offers more insight into his journey and the world in which he became smitten — and obsessed.

Q: Your memoir highlights the tension between hope and reality in Hollywood. How did your perspective on success and fame evolve over the years, and how did it shape your approach to writing?

A: As with most writers, I was enamored with stories as a child, and storytelling as a pursuit began to feel real in my 20’s. Seeking fame did not. I never thought of going to Hollywood. I never considered making movies until I was doing so. I loved stories. Despair and isolation drove me to tell them, first on paper and then on film. I only started thinking about fame when I began working with famous people, and I understood how attainable it can be for those willing to work at it, but the work requires steel nerves, crocodile skin and an iron stomach. When you are pursued for your stories, then paid for them, that is success.

Q: Tell the Story paints a vivid picture of the highs and lows of screenwriting for the Hollywood elite. Can you share a particularly memorable moment when a project’s failure taught you something valuable about the industry or yourself?

A: I have several memories of projects halted because a studio executive is replaced, and the incoming doesn’t want to inherit a predecessor’s slate. This is regardless of what stage of development or even production they have reached. Sometimes a director or actor leaves and initiates a wave of departing creatives or department heads. This can happen for any variety of reasons. It is common enough that most filmmakers learn early in our careers that it becomes a mistake to take any level of early success or failure too seriously, for we all have that experience, and no one is immune to suddenly finding themselves out of work, out of favor, or both.

Q: Hollywood is notorious for its unpredictability. How did you maintain your creative drive and resilience when facing repeated setbacks or rejections?

A: Unpredictability is part of what makes it fun. You never know what to expect. Like every Hollywood veteran, I have numerous stories about that — some exciting, some funny, some disturbing. One rewarding experience outshines a dozen disappointments. Making a film with people you respect is memorable, even if the result is not. Among a crew of hundreds, everyone must do their job well, which is a massive achievement. Sloppy work is obvious on the screen, and every pro sees it. The audience might not realize why, but when the film is flawed, they know it. Considering all the creative, physical and financial elements that must fall into place simultaneously, a truly good movie is something of a miracle.

Q: Given the rollercoaster of emotions in your career, how did your relationship with storytelling itself change — was there ever a time when you considered stepping away from writing?

A: When I came to Hollywood, I had never written a screenplay. But I knew that a compelling script, paired with confidence and conviction, would get a first-time director a shot. It worked for me, but as it so often does, financing fell short. A successful television producer read my script and hired me to write for his show, which soon built on itself. I wanted to direct movies, but I wasn’t interested in making other people’s screenplays, so I left TV and chose to focus on writing for film. I would have chosen to try writing novels rather than seek work as a director for hire, but I found traction as a writer and producer for film.

Q: In the book, you describe Hollywood as both alluring and unforgiving. Do you think this paradox is what keeps so many creatives drawn to it despite the risks?

A: I think the paradigm has shifted dramatically. When I arrived, only a handful of university programs were teaching film. Now there are hundreds, with thousands of talented, enthusiastic young filmmakers worldwide making films on their phones, flooding not just studios and streamers with their work, but YouTube and social media as well. Some of these artists are earning up to seven figures a year through advertising, without a need for a distributor or even publicist. It is the future, which is extremely alluring for young artists, with limited risk. Any creative field can be unforgiving, as those who pursue them are fully aware, but artists willfully find the validation of peer recognition to be worth the emotional risk.

Q: For aspiring screenwriters or filmmakers, what advice would you offer about navigating the industry’s unique mix of hope, ambition, and inevitable disappointment?

A: Disappointment is less powerful than inspiration. Every project has a shelf life, including those with money attached. As a writer or filmmaker, you can only focus on the immediate goal of getting a film made and maintain that focus until obstacles become unmanageable. At that point, start something new. Sometimes dead projects are resurrected if an actor, director or producer remembers a script and wants to revisit it. It doesn’t happen very often, but it can. My advice is to act like a shark and keep moving for oxygen. Think of a story or theme that interests you and bring it to life. When you start waking up with fresh ideas in your head, the disappointment is soon left behind.

Q: Your story touches on the allure of fame. How do you feel fame influences the creative process, and do you think it ultimately helps or hinders authentic storytelling?

A: Most writers I have known have never been driven by the pursuit of fame, and, if ever, will only show affect once it’s bestowed on them, which is often accidental. It is also extremely limited for writers. Only cinephiles notice who wrote notable screenplays, or even who directed the movies. In the film world, fame is essentially for actors, sometimes directors, and occasionally for adapted novelists if the publicity calls for it. Rarely for screenwriters. But having authored a film which is destined to remain in the public consciousness for generations? That is every screenwriter’s dream. The distinction of having created a piece with an immortal power to move; to inspire. That is the greatest of all rewards.

Tell the Story is available for purchase on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.

RELATED POSTS:

Hollywood Screenwriter Flirts with Fame in Stunning Memoir

Terrell Tannen has written, directed and produced feature films, television, documentaries, and shorts for nearly fifty years. His credits include The Boogey Man, A Minor Miracle, Shadows in the Storm, Gospel Hill, Honor Bound, and dozens of commissioned screenwriting assignments around the world. His commentaries, stories, and essays have appeared in Wall Street Journal, The New Yorker, Washington Post, and The Lancet. His first memoir, When Blood Is Gone, was published in 2013. An excerpt, Finding John Huston, appeared in The New Yorker Culture Desk. Excerpts from Tell the Story: A Hollywood Odyssey have appeared in The Wall Street Journal (When Pele Met the Public at the Chart House) and Literary Hub (Your Meals in Life are Numbered.)

Terrell Tannen has written, directed and produced feature films, television, documentaries, and shorts for nearly fifty years. His credits include The Boogey Man, A Minor Miracle, Shadows in the Storm, Gospel Hill, Honor Bound, and dozens of commissioned screenwriting assignments around the world. His commentaries, stories, and essays have appeared in Wall Street Journal, The New Yorker, Washington Post, and The Lancet. His first memoir, When Blood Is Gone, was published in 2013. An excerpt, Finding John Huston, appeared in The New Yorker Culture Desk. Excerpts from Tell the Story: A Hollywood Odyssey have appeared in The Wall Street Journal (When Pele Met the Public at the Chart House) and Literary Hub (Your Meals in Life are Numbered.)

Before moving to Hollywood, Mr. Tannen worked on staff at the Joint Committee on Congressional Operations, U.S. Congress, and as a free-lance journalist and documentary filmmaker in Washington, D.C.